The political and media landscapes in France are both undergoing a profound reconfiguration. How do these two shifting environments interact on social networks today? In an effort to answer this question, we partnered with the company Graphika to develop a visualization of the new French political-media landscape, as it manifests itself on Twitter. We developed a map of the 15,000 most closely interconnected accounts on this social network, including those of 1,019 leading French political figures. Algorithmic analysis of this map revealed several account clusters, such as that of the media and journalists, or of individuals identifying to various French political trends.

The principal conclusions that can be drawn from this map’s analysis are as follows:

These results indicate that in France the “traditional” media still act, at least to some extent, as a common agora: a space dedicated to displaying facts and discussing ideas to which social network users of all political persuasions are more or less strongly connected. Our results suggest, however, that the French political-media landscape is not immune to gradual fragmentation at its extremes.

The French political landscape is undergoing a period of reconfiguration. The emergence of the presidential party, La République En Marche (LREM), has profoundly weakened the traditional socio-democratic left (Parti Socialiste; PS) and is forcing the traditional right (Les Républicains; LR) to reposition itself. Parties at the extremes of the political spectrum are attracting a significant share of the French electorate, as evidenced by the results obtained by the extreme right (Rassemblement National; RN, formerly Front National) and the extreme left (La France Insoumise; LFI) in the first round of the last presidential election.

Parallel to this reshaping of the established left-right political spectrum, the “Yellow Vests” movement, emerging at the end of 2018, aggregates diverse political demands centering around a populist “anti-elite” agenda that transcends traditional cleavages. Indeed, both RN and LFI sympathizers, as well as non-voters, are over-represented within the "Yellow Vests” movement.1

The French media landscape is also undergoing profound change. According to a recent study by the Institut Montaign 2, the media space today is structured around four groups of media outlets exhibiting distinct behaviors:

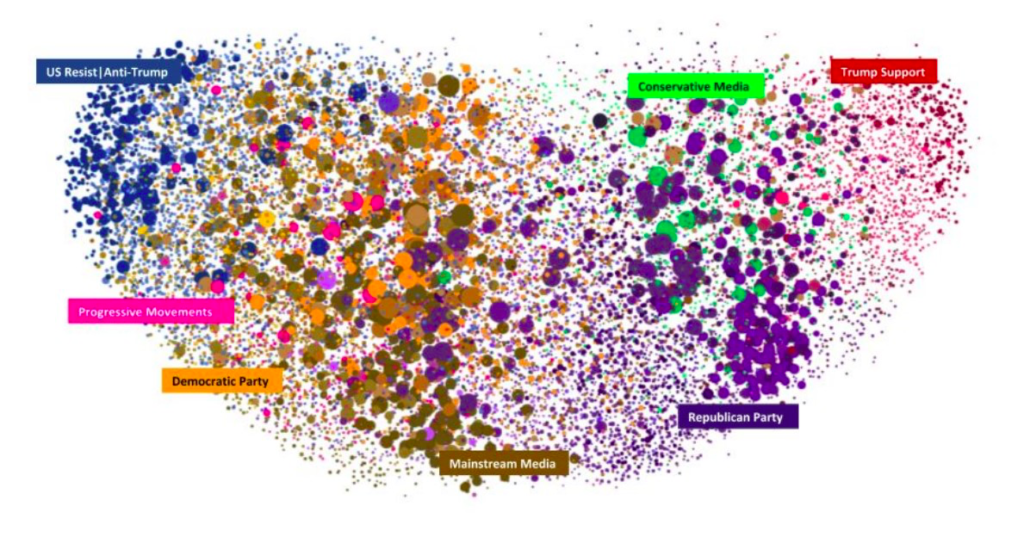

This study by the Institut Montaigne shows that, on the whole, the French media landscape is not strongly polarized, contrary to what can be observed, for example, in the United States. In other words, if the “traditional” media that make up the “heart” of the media space represent “moderate” political sensitivities on both sides of the left-right spectrum, this does not result in a pronounced cleavage between these two media poles. Indeed, we observe that “traditional” media outlets associated with various political sensibilities refer to and quote one another.

On the other hand, these media outlets almost never refer to content published by media outlets outside the “heart”. Therefore, if there is a clear divide within the French media landscape, it does not exist within the “traditional” media space, but rather between it and the “satellite” and “crown” media spaces. These emerging media are characterized as much by their relative isolation from the “heart” of the media space as by their editorial line, which often carries more obvious and marked ideological leanings, and which is often more radical than that of the “traditional” media.

How does the shifting French political landscape interact with this new structure of the media space? According to their positioning in the media space, how do politicians on different sides of the political spectrum and their supporters interact with each other and with the media and journalists? Are there, as we observe in the United States or, to a lesser extent, in Spain, two parallel political-media spaces within which politicians and their base gravitate in relatively closed circles around media outlets committed to their ideology, without communicating with or informing themselves from those of the opposite side?

To answer this question, we developed a visualization of the new French political-media landscape, as it was taking shape on Twitter at the turn of 2019-2020 – a time period that proved particularly pertinent for this analysis, as it was rich in social and political events (preparation of the reform of the pension system, large-scale social movements against this future reform, and the last outbursts of the “Yellow Vests” movement).

Utilizing Twitter data allowed us to measure the relationships between politicians, their supposed “sympathizers” and the media using proven quantitative methods. While it is important to note that Twitter is not an accurate and representative reflection of society as a whole, most leading French politicians are active on the platform, and many of their supporters follow them on this social network. Likewise, all media outlets have a Twitter account, as do a large number of journalists. It therefore seems legitimate use this social network to analyze the new political-media landscape in France.

This study was conducted in partnership with Graphika, a company specializing in social network analysis. In order to understand the relationships between politicians, supporters and the media on Twitter, we compiled a list of 1,019 leading French political figures active on the platform (members of parliament, leading figures from political parties, members of the government, presidents of regions and departments, mayors of large municipalities).

From this initial list, Graphika generated a map of the French political-media landscape, as it was structured between December 9, 2019 and January 8, 2020, incorporating the Twitter accounts that were most interconnected with those of the political figures initially identified. The media actors and “political sympathizers” who appear on this map – accounts that were therefore not included in our initial list – were selected by an algorithm on the basis of the Twitter interactions they have with these 1,019 political actors.

More precisely, the algorithm searched Twitter for any accounts following at least one of the accounts included in our initial list. Among the accounts identified in this manner, the algorithm retained for the final map only those that were most closely linked to the initial 1,019 accounts – namely, the accounts that followed the largest number of the political figures included in our initial list.

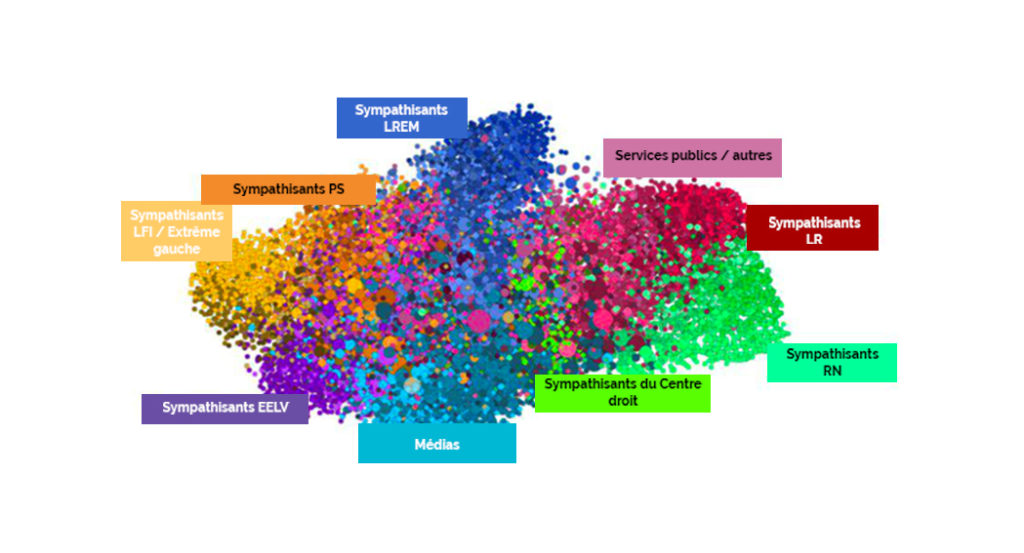

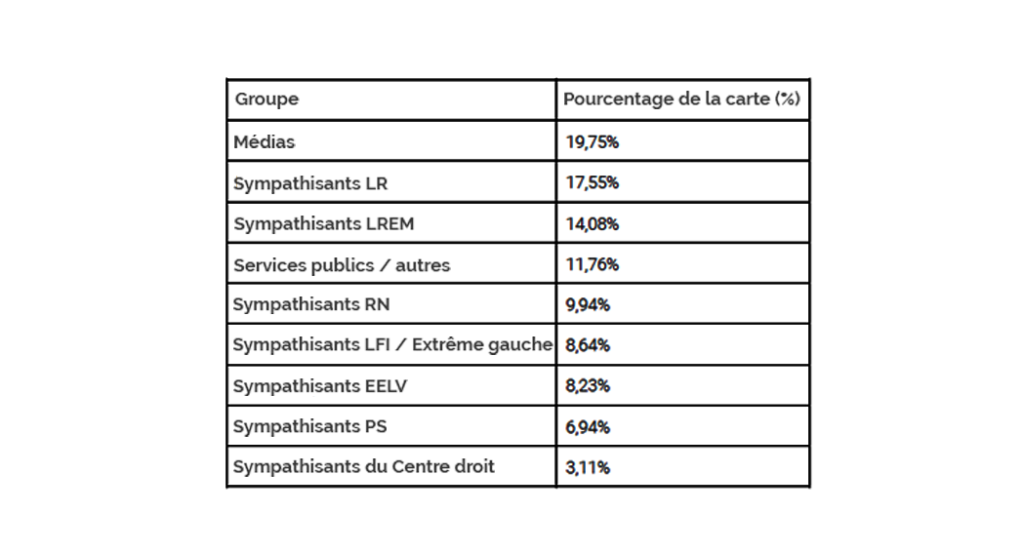

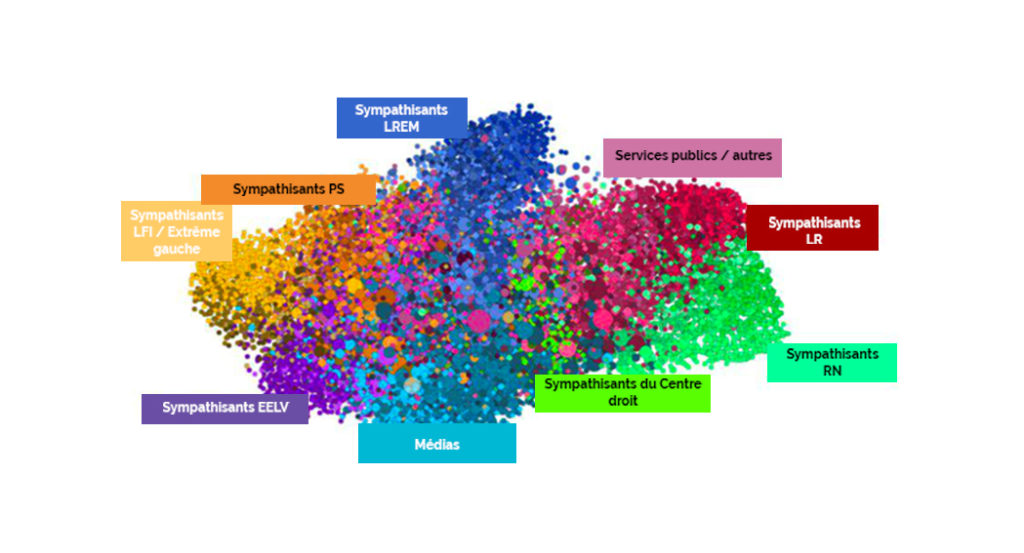

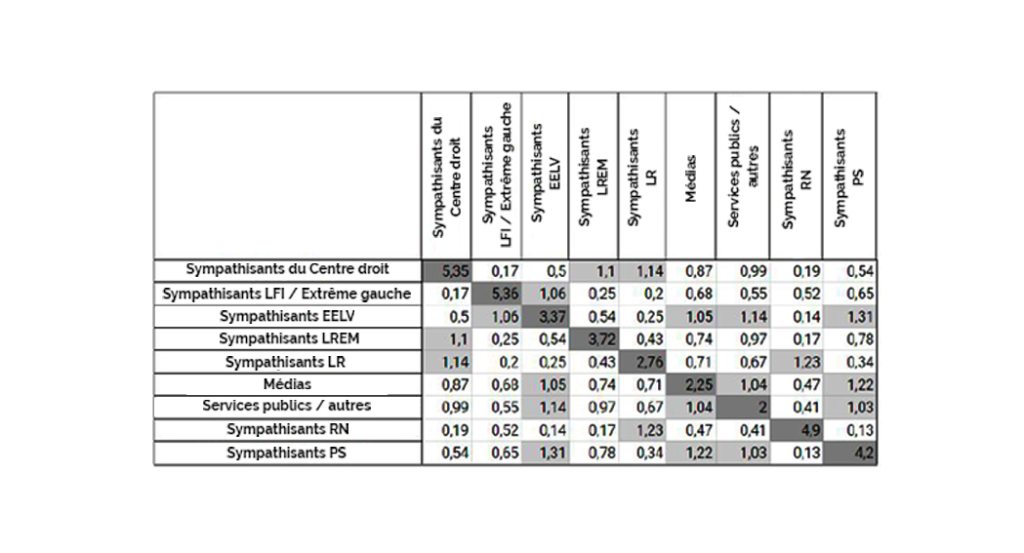

The resulting map of the political-media landscape consists of 15,000 accounts, which were then grouped by Graphika's algorithm according to the similarities between their respective subscription lists. Lastly, an algorithmic analysis allowed us to label these groups, resulting in the identification of the nine groups indicated in Table 1.

It is important to note that the accounts classified by the algorithm under a given political label are not necessarily those of members of that party. The algorithm categorized them as such on the basis of the accounts to which they themselves subscribed. For example, the algorithm classified an account under the label of a given party because it subscribed to a large number of accounts belonging to political figures of that party, and to other accounts also following these same political figures. The hypothesis underlying this approach is that such an account can be considered as a “sympathizer” of the party in question, due to the considerable interest it shows in the political figures of this party, and in other accounts that eagerly follow these figures.

The accounts affiliated with the media group (none of which were included in our initial list, which only considered political figures) correspond to accounts exhibiting highly similar subscription lists, which the algorithm identified as being the accounts of journalists or media outlets.

A visual inspection of the algorithm’s selection and labeling of accounts confirms its overall relevance.

The visualization of the French political-media landscape resulting from our study is shown in Figure 1.

In order to better understand this visualization, Figure 2 highlights the accounts belonging to the media cluster (i.e. accounts of journalists and various media outlets).

As this map illustrates, the media landscape in France is not, as a whole, strongly polarized. Indeed, the geographical proximity of accounts belonging to the media cluster, visible in Figure 2, indicates that most of these accounts interact with one another (many of these accounts follow each other). These findings are in line with those of the Institut Montaigne’s report on the absence of significant media polarization in France.

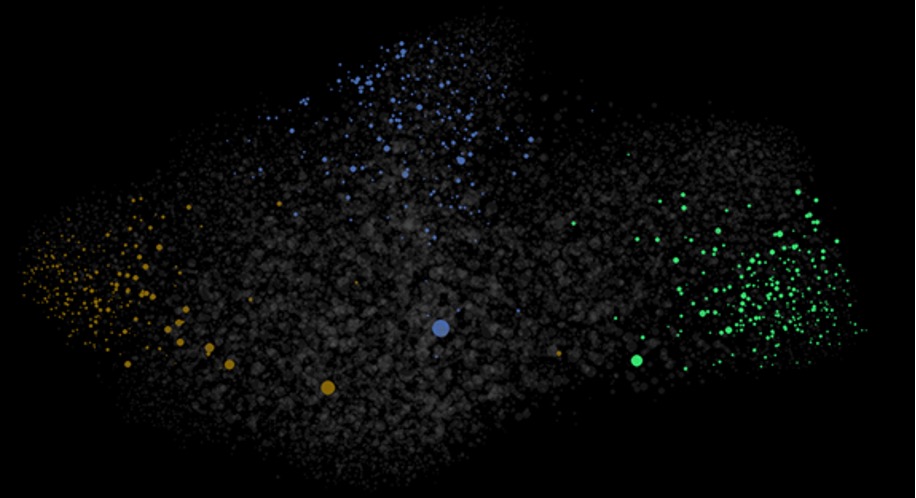

Meanwhile, Figure 1 shows that every political group is connected to the media cluster. Thus, in France, there is no clear divide in the political-media environment. For comparison, Figure 3 illustrates the situation in the United States, where, on the contrary, we observe the presence of two parallel political-media spaces that are poorly interconnected. This reflects the separation of American society into two large antagonistic ideological camps, whose members inform themselves and communicate with each other mainly through their own respective media channels.

However, it is important to note that not every political group identified in Figure 1 is connected to the media cluster with the same intensity. As can be seen in Table 2, the groups labeled RN (extreme right) and, to a lesser extent, LFI / Extrême Gauche (extreme left), are less closely connected to the media cluster than other political groups.

Our analyses also show that the most influential media outlets in the French political-media landscape remain by and large those of the “traditional” media (as opposed to “satellite” or “crown” media outlets). This is illustrated by the fact that “traditional” media outlets are more interconnected to the accounts of politicians and their supposed “sympathizers” than other types of media. Moreover, among all media accounts, those of the “traditional” media are mentioned most frequently, and their tweets are the most shared (see Table 3).

These findings must, however, be nuanced. First, certain “satellite” and “crown” media outlets with strong political leanings are highly followed – and therefore influential – within particular groups but carry little to no weight outside of these circles. This is the case, for example, of L'info libre or Radio Courtoisie, both of which were placed into the RN group rather than the media group by Graphika’s algorithm. This is due to the fact that these media outlets are closely interconnected with accounts belonging to the RN group and very weakly connected to accounts from the media group, or with other accounts present on the map. We observe a similar phenomenon on the other side of our map, where “crown” media outlets such as Alternatives Économiques and Politis are integrated into the EELV/Droits Humains group rather than the media group.

Second, our findings put into question the central role that “traditional” media still seem to play in the French political-media landscape. If these media remain overall the most mentioned by all of the Twitter accounts include in our map, they are not always mentioned in a positive way.

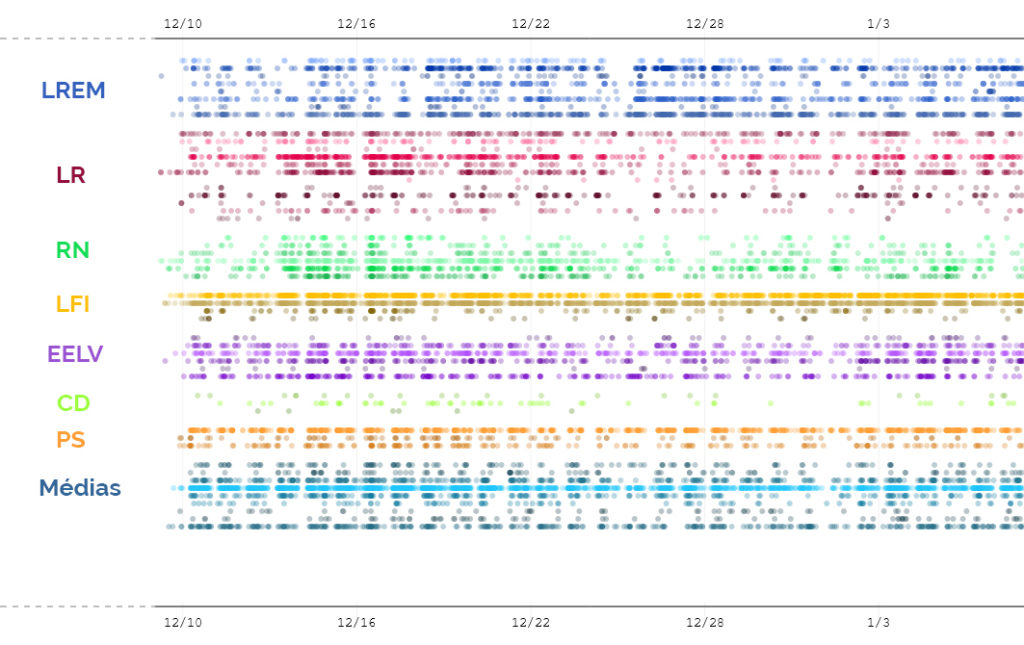

Let us take the example of Le Monde – a newspaper often described as a reference point and located in the center-left of the political spectrum – which is, among all identified media, the outlet that was mentioned most throughout the time period under consideration (see Table 3, second column). Moreover, our results show that this newspaper is mentioned in a relatively homogeneous way over time by all of the political group present on our map (see Figure 4).

In order to determine whether the tone of the mentions of Le Monde differs according to the groups from which originate, we conducted a qualitative analysis by sampling of tweets mentioning Le Monde. This analysis showed that, during the time period covered by our study, most groups mention Le Monde as a reference or as a source for sharing news, with the exception of the RN group, which primarily mentions Le Monde in order to criticize it.

These criticisms can be split into two groups:

We should note that a similar qualitative analysis of Tweets mentioning the Figaro – a newspaper generally considered to hold a right or center-right editorial stance – does not show an above-average amount of criticisms emanating from the most left-leaning group on our map (group labeled LFI / Extrême Gauche).

The results of these qualitative analyses should, however, be taken with caution, as they only consider a time period of one month. This is an important caveat, given that the virulence of the criticisms stemming from various groups likely depends on current events and their media treatment. Nevertheless, we can state with certainty that while “traditional” media remain the media sources that are most frequently mentioned by every political group present on our map, they are regularly mentioned in a critical manner.

Lastly, while the media and journalists clearly occupy a central position on our map, in that all of the political groups identified are to some extent connected to it, not all of the accounts within these groups have the same proximity to the media cluster. In this respect, we see that leading political figures (party leaders, in particular) are closely connected to the media cluster, whereas this is not the case for their presumed closest “sympathizers”.

To illustrate this point, Figure 5 shows the Twitter accounts of Jean-Luc Mélenchon, Emmanuel Macron, and Marine Le Pen, as well as those of the individuals most closely connected to the accounts of these political figures. We observe that the accounts of these political leaders are located towards the center of the bottom half of the map, which corresponds to the zone occupied by the media cluster (see Figure 2). The accounts of their supposed “sympathizers” are, however, located in the periphery of the map, far from the media cluster.

This indicates that different actors utilize Twitter in different ways: a political leader will seek to communicate with a large number of actors in the network and to maintain a strong proximity with the “traditional” media, whereas political “sympathizers” will tend to remain focused on their own group – within which there may potentially be a certain number of “satellite” and “crown” media outlets. The high concentration of “traditional” media outlets at the center of the map could therefore reflect the frequent accusations of these outlets remaining in a closed circle among themselves.

The principal conclusions that can be drawn from our study are as follows:

These results indicate that in France the “traditional” media still act, at least to some extent, as a common agora: a space dedicated to displaying facts and discussing ideas to which social network users of all political persuasions are more or less strongly connected.

And yet, it is important to note that the significance of this common media agora is perhaps somewhat exaggerated by the methodology employed in our study. Indeed, the map presented in this report was generated from an initial list of prominent French political figures (see section 3.2). The map being structured around the media cluster is therefore a direct result of their Twitter behavior. But as we have shown, the positioning of political figures in relation to the media cluster is not representative of their supposed “sympathizers”, whose positions are far more peripheral. These Twitter users are therefore only indirectly connected to the media cluster via the political leaders they follow.

In conclusion, let us note that the French political-media landscape may not be immune to gradual fragmentation at its extremes. Indeed, the groups located furthest to the right and, to a lesser extent, furthest to the left on our map are less closely connected to the common media agora than the other political groups identified. In this context, “peripheral” media outlets could possible gain in influence among groups located at the extremes of the political spectrum, to the detriment of the “traditional” media. This hypothesis of a progressive fragmentation of the French political-media landscape can only be corroborated or refuted by regular monitoring of how its structure continues to evolve in the future.

To cite this report: Cordonier, L., Brest, A., Guedj, N., & Ruault, T. (2020). Visualization of the new political-media landscape in France. Study by the Fondation Descartes, https://www.fondationdescartes.org/en/2020/11/visualization-of-the-new-political-media-landscape-in-france/